| Scott S. Reuben, MD Professor of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Department of Anesthesiology Baystate Medical Center and the Tufts University School of Medicine Springfield, MA Preventing postthoracotomy pain syndrome following surgery Pain following thoracic surgery has been reported to be among the most intense clinical experiences known [58]. The nociceptive pathways that are responsible for postthoracotomy pain are still poorly understood [59]. Possible sources of nociceptive input that may contribute to postoperative pain following thoracic surgery are multiple and include the site of the surgical incision, disruption of the intercostals nerves, inflammation of the chest wall structures adjacent to the incision, pulmonary parenchyma or pleura, and thoracostomy drainage tubes [60]. Unrelieved acute pain following thoracic surgery can not only contribute to postoperative pulmonary dysfunction, [61] but may also contribute to the development of postthoracotomy pain syndrome [1,2]. Postthoracotomy pain syndrome is defined as pain that recurs or persists along a thoracotomy incision for at least 2 months following the surgical procedure [62]. The true incidence of postthoracotomy pain syndrome is difficult to determine with a reported range from 5% to 80% [63]. Different definitions used to describe and assess pain, lack of large, prospective studies, small sample size, varying surgical techniques, varying perioperative management, and different periods of follow-up care have all contributed to the difficulty in determining the true incidence of this post-surgical pain syndrome [63]. Nonetheless, it has been estimated that half of all patients still alive 1-2 years after thoracotomy will suffer with persistent chest wall pain [64]. Further, as many as 30% of patients might still experience pain 4 to 5 years after surgery [64]. The exact mechanism for the pathogenesis of postthoracotomy pain syndrome is still not clear. Similar to chronic donor site pain, it has been suggested that both neuropathic and myofascial nociceptive pathways contribute to the development of postthoracotomy pain syndrome. While damage to cutaneous or deep (muscle, joint and viscera) tissue is typically associated with peripheral inflammation, damage to neural structures often leads to pathological pain [5]. Damage to intercostal nerves during thoracic surgery leads to neural degeneration, neuroma formation, resulting in the generation of spontaneous neural inputs [5]. Evidence suggests that although nociceptive and neuropathic pain depends upon separate peripheral mechanisms, they are both significantly influenced by changes in central nervous system function [5]. The resultant neuroplastic changes in the central nervous system have the capacity to contribute to persistent pathological pain following surgery [5]. A variety of preemptive or preventative analgesic techniques have been utilized in an attempt to reduce sustained nociceptive input into the central nervous system and concomitant acute and chronic pain following thoracic surgery. In a retrospective review of 1000 thoracic surgery patients, Richardson et al. [65] assessed the efficacy of acute postoperative pain on the incidence of postthoracotomy pain syndrome at two months following surgery. The use of systemic opioids alone was associated with a 23.4% incidence of postthoracotomy pain syndrome [65]. Interestingly, the use of intraoperative intercostal neurolysis with a cryoprobe increased the incidence of chronic pain to 31.6% [65]. In contrast, the use of continuous paravertebral infusion of bupivacaine in conjunction with systemic opioids decreased the incidence to 14.8% (110). Further, the addition of an NSAID to this analgesic regimen reduced the incidence of postthoracotomy pain syndrome to 9.9% [65]. These findings highlight the importance of utilizing a multimodal analgesic regimen for the prevention of acute and chronic post-surgical pain. In addition, even when a perioperative local anesthetic block is utilized, nociceptive afferent pathways to the CNS can still be activated resulting in the release of “stress response” mediators leading to central sensitization (Figure 5) [65].

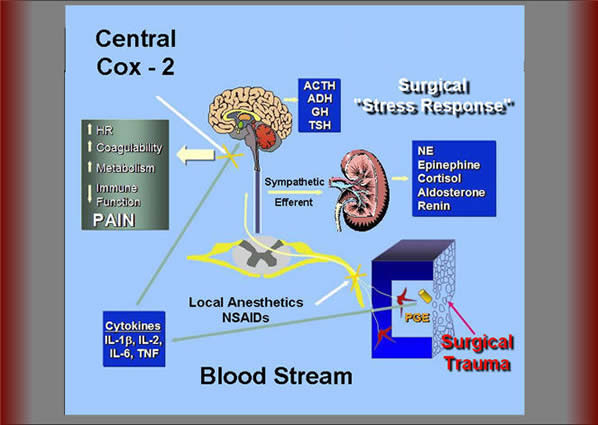

Figure 5. Surgical trauma results in the release of a variety of inflammatory mediators including prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). There appears to be two forms of nociceptive input from peripheral inflamed tissue to the central nervous system which can trigger the release of “stress response” mediators. The first is mediated by neural activity innervating the area of injury which may be reduced with local anesthetic neural blockade and/or peripherally-acting COX-2 inhibitors. The second pathway is humorally mediated, in which interleukins reach the central nervous system via systemic pathways leading to upregulation of COX-2 in the central nervous system. This latter pathway is not affected by regional anesthesia and only blocked by centrally acting COX-2 inhibitors NE=norepinephrine; ACTH=adrenocorticotropic hormone; ADH=antidiuretic hormone; GH=growth hormone; TSH=thyroid-stimulating hormone; TNF=tumor necrosis factor; IL=interleukins; NSAIDs=nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. There appears to be two forms of nociceptive input from peripheral inflamed tissue to the CNS [53]. The first is mediated by neural activity innervating the area of injury which may be reduced with local anesthetic neural blockade and/or peripherally-acting COX-2 inhibitors (Figure 5). The second pathway is humorally mediated, in which interleukins reach the CNS via systemic pathways leading to upregulation of COX-2 in the CNS. This latter pathway is not affected by regional anesthesia and only blocked by centrally acting COX-2 inhibitors [53]. We have demonstrated that CNS levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) are still up-regulated following lower extremity surgery despite an adequate spinal anesthetic [66]. Further, the administration of a centrallyacting COX-2 inhibitor to these patients resulted in a significant decrease in CNS PGE2 levels and improved postoperative analgesia [66]. McCrory et al. [67] confirmed the analgesic benefit of adding a centrally-acting COX-2 inhibitor with neuraxial analgesia for post-thoracotomy pain. This randomized, prospective, double-blind study evaluated the analgesic efficacy of ibuprofen (peripherally-acting NSAID), nimesulide (centrally-acting NSAID), or placebo in conjunction with neuraxial analgesics. This study revealed a significant reduction in postoperative pain and opioid use with the centrally-acting NSAID, nimesulide, compared to either ibuprofen or placebo. This pain reduction correlated with a significant reduction in CSF PGE2 observed in the nimesulide group which was not seen with either placebo or ibuprofen. In a retrospective study of 159 patients undergoing posterolateral thoracotomy, Hu et al. [68] examined the effects of thoracic epidural analgesia on the incidence of postthoracotomy pain syndrome. One hundred nineteen patients received thoracic epidural anesthesia in conjunction with general anesthesia and 40 patients received only general anesthesia. Thoracic epidural analgesia was initiated prior to surgical incision and maintained intraoperatively with an infusion of bupivacaine 0.5%. Following surgery, these patients were administered epidural morphine every 12 hours for the first 3 days. These authors reported a similar incidence in ostthoracotomy pain syndrome in the epidural analgesia group (42%) compared to the general anesthesia group (39%). In contrast to these findings, Obata et al. [69], in a prospective, randomized, double-blind study, revealed a significant analgesic benefit when epidural analgesia was initiated prior to thoracic surgery. These investigators compared the analgesic effects of a continuous thoracic epidural infusion of mepivacaine initiated 20 minutes prior to surgery or at the completion of surgery and continued for the first 3 postoperative days. This study revealed a significant reduction in both acute and chronic postthoracotomy pain at 6 months following surgery in the pre-compared to the postincisional epidural analgesia group. The beneficial effects of epidural analgesia following thoracic surgery were confirmed in a more recent prospective, randomized, double-blind study performed by Senturk et al. [70]. These investigators compared the analgesic effects of three different analgesic techniques: (1) thoracic epidural analgesia initiated before or (2) after surgical incision and (3) intravenous patient controlled analgesia (PCA) on acute postoperative pain and the incidence of postthoracotomy pain syndrome 6 months following surgery. Patients in the pre-thoracic epidural group reported significantly less pain compared with the post-thoracic epidural or the PCA groups for the first 48 hours following surgery. The incidence of postthoracotomy pain syndrome was also significantly lower in the pre-thoracic epidural group (45%) compared to either the post-thoracic epidural (63%) or the PCA (78%) groups. Although both Obata et al. [69] and Senturk et al. [70] demonstrated a beneficial effect with the preemptive administration of epidural analgesia for thoracic surgery, Ochroch et al. [71] were unable to report similar findings. In a prospective, randomized, double-blind study of 157 patients, these investigators examined the analgesic efficacy of thoracic epidural analgesia initiated prior to surgical incision or at the time of rib approximation. Overall, there were no differences in pain scores or activity level during hospitalization or after discharge between the two groups. Further, the number of patients reporting pain 1 year following surgery was similar in between the two groups. From these studies, it can be concluded that the method of perioperative pain management has a variable effect on the incidence of postthoracotomy pain syndrome. The reason for this variability may be explained by the multiple sources of nociceptive afferent pathways involved in the perception of pain following thoracic surgery [60]. These pain sources may be conveyed to the central nervous system via somatic nerves (intercostal nerves), phrenic nerve, cranial nerve (vagus nerve), the sympathetic nervous system, the parasympathetic system, and the brachial plexus [63]. It has been demonstrated that thoracic epidural analgesia is unable to abolish somatosensory evoked potential resulting from thoracic dermatomal stimulation, suggesting that this regional technique may be insufficient in blocking all nociceptive pain pathways [72,73] Therefore, the use of regional blockade by itself is insufficient in providing complete pain relief and preventing central sensitization of the nervous system following thoracic surgery. A multimodal analgesic regimen, in which regional blocks are combined with NSAIDS and other analgesics, as described by Richardson et al. [65], may provide for a reduction in both acute and chronic pain following thoracic surgery. Future prospective, randomized studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of utilizing preventative multimodal analgesic techniques on the incidence of postthoracotomy pain syndrome. PREVENTING OTHER CHRONIC PAIN DISORDERS Phantom limb pain (English) Chronic donor site pain (English) Postmastectomy pain syndrome (English) Part II: Algorithm for Perioperative Management of CRPS Patients Part III: Highlights for Patients References |