USE OF OPIOIDS (NARCOTICS) IN CHILDREN

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

We're going to turn to our final and very important topic here, which relates to the use of opioids in children.

Now, for that, we have really...we've really got great, great people here. We have Dr. Alyssa LeBel from Harvard Medical School. What makes her rather unique is she's collaborated with some of the great people in pain. For example she was with Dr. Schwartzman for a while and they did that landmark paper on spreading RSD patterns. Now she is at Harvard working with another outstanding scholar in the field of pain as particularly as it relates to children, Dr. Charles Berde. She is doing some very important research on RSD in children. Dr. LeBel is primarily a Neurologist, but she is in the Department of Anesthesia because of her special expertise as it relates to the pharmacology and so forth in the area of Pain Management. Um, Dr. LeBel?

Dr. Alyssa LeBel:

Hello!

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Hello! Share with us some of your vast experience, I know it is quite vast, share with us your experience in dealing with the issue of the use of opioids in children that have chronic pain, please.

Dr. LeBel:

Thank you very much for that very kind introduction, and I just want to thank all our colleagues and the staff of this conference for providing such excellent presentations. Many of these topics are, of course, applicable to their pediatric correlates, but I wanted to talk about pediatric pain in terms of what special aspects are presented with this group.

So, first I just wanted to just show a photo of one of our patients who also, although not seen in this photo, had lower extremity involvement at the time of her initial presentation; and of course the effected limb in this photo at this time is on the right side.

So, first I just wanted to just show a photo of one of our patients who also, although not seen in this photo, had lower extremity involvement at the time of her initial presentation; and of course the effected limb in this photo at this time is on the right side.

To briefly review, turning toward the definition of CRPS, again, just since we've discussed so many issues so far. CRPS, or complex regional pain syndrome, is defined by clinical phenomena. The specific pathophysiology of this disorder is really still yet to be elucidated, but Neuro Science holds many promises for that. It's likely to involve multiple mechanisms and to multiple levels of the pain transmission and the pain modulation systems, which will welcome a number of treatment strategies to our armamentarium.

The clinical features, associated with CRPS are just to briefly review: neuropathic pain; abnormal regulation of blood flow and sweating; edema, trophic changes of the skin and appendages; and active and passive movement disorders that have been well described by Dr. Schwartzman.

In the pediatric population, there are also unique epidemiologic features. The epidemiology of CRPS, as well as other chronic pain syndromes in children is, unfortunately still not well documented. I will direct your attention to a report by Dr. Robert Wilder, who is now at the Mayo Clinic, who reported more than 395 cases in the literature as of 1996:

At Childrens' Hospital in Boston, we receive about two new referrals for patients who are less than 18 years with features of CRPS every week, and generally the patients that come to us have failed conventional therapy. What's unique about the pediatric presentation is that it's very rare first to see this presentation at all before 6 (six) years of age. The most common age of onset is 10 to 12 (ten to twelve) years, and continues into young adolescents.

In the pediatric population as opposed to the adults, the lower extremity is more generally involved than the upper extremity. In fact, in our collection of data here at this institution, we see a 6 to 8 over 1 ratio (six to eight over 1 ratio) of lower extremity to upper extremity involvement. Girls are effected 6 (six) times more often than boys. The signs and symptoms often spread from one extremity to another, and frequently in the pediatric population, these episodes of pain associated with the other physiologic changes in the clinical features that define the entity are recurrent. With each occurrence after the original presentation, the presentation is usually much less severe and more brief and more readily treated by our current treatment strategies.

Resolution in the pediatric population is much faster and more robust with physical therapy, behavioral medicine intervention, cognitive and behavioral medicine treatment, and sometimes the addition of the transcutaneous nerve stimulator. And in the pediatric population, thankfully, the prognosis is much more favorable despite duration of signs and symptoms. So, although the pediatric patient may have a longer period overall carrying this diagnosis, the extent of their disorder is often less than an adult may present with. They have less severe disease and more readily treated disease.

Now, turning toward opioids. We readily use opioids in the pediatric population, certainly for somatic and cancer pain, and we have to individualize as happens in the adult population, their use for non-malignant pain problems. As Dr. Kiefer had mentioned, you know the research data is very limited for the use of opioids in non-malignant pain in general and is especially true for the pediatric population. We have many anecdotal reports and a lot of experience with the use opioids with intraspinal administration. Some effective uses of opioids, some examples in patients with CRPS include: when we use our opioid doses at times of physical therapy, knowing that physical therapy is still the gold standard of treatment in these patients; and when we use brief courses of sustained opioids followed by a taper when there's onset of severe pain in this pediatric population.

The role of opioids in CRPS is somewhat restricted and in the pediatric population, especially where comprehensive approach is needed and a family oriented as well as patient oriented direction is taken, we need to use opioids as part of a multidisciplinary approach to pain management.

In terms of pharmacology of opioids, the pharmacology is very similar to that of adults, as are the side effects described by Dr. Kiefer. And the pharmacology is similar for pediatric patients that are previously full-term infants from about 3 (three) to 6 (six) months on. So, our only concern in adjusting the pharmacology of opioids is in regard to the premature infant in the first year of life and in the neonate.

I'd like now to say that opioids are not the primary therapy for chronic pediatric neuropathic pain. Dr. Kiefer and Dr. Kirkpatrick have appropriately emphasized that the NMDA receptor antagonists as being a very important area of research and increased clinical trial. In the pediatric population we use these non-opioid therapies as well, which include such things as the ion channel blockers; another very important area of research includes the sodium channel blockers such as the anti-epileptiform agents Trileptal, Neurontin; and the N-type calcium channel agents, which also includes Neurontin as well as the NMDA receptor blockers that are primarily glutamate antagonists, such as ketamine and dextromethorphan.

There is some work that is directed toward specific opioid receptor agonists, but this is still quite early. Looking at these receptors...as Dr. Savage did, she presented the receptors in terms of kappa versus mu receptor agents. Clonidine, as an Alpha-2 adrenergic adjuvant for treatment of pain is often used in combination with our opioids intra-spinally as well as orally, allows us to use much less opioid with less side effects. And inflammatory mediator antagonists, things that antagonize cytokines like anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha, which is being used in inflammatory states in adults, may hold great promise for the neurogenic inflammation of CRPS.

I wanted to bring up next some research that has occurred with Dr. Berde and again Dr. Wilder, back in 1992 regarding the spinal infusion of opioids and local anesthetics. And this particular study that I'd like to talk about that happened in 1992 looked at combined infusions, via a lumbar epidural, because again remember our population is mostly lower extremity, or paravertebral sympathetic indwelling catheters, in a group of patients who had persistent pain despite very extensive outpatient physical therapy and cognitive and behavioral therapy. And, a subgroup during this study showed a very interesting phenomenon that again shows somewhat of a unique neural substrate in pediatric patients as opposed to adults, at least as has been reported. But there was a marked right-shift in the epidural and spinal local anesthetic dose response curves. There are some patients that required very high doses of local anesthetics to even achieve any pain relief, or, at a level that one would expect you'd have a complete spinal block, they just barely had a little bit of pain relief. And that was a very interesting observation and something that we've continued to explore with the pediatric patients.

A subgroup reported pain despite achieving complete sensory, motor and sympathetic blockade, prompting our colleagues to suggest a supratentorial diagnosis, which in part may be true, but pain is a very distributed system, and there are supratentorial aspects of pain that create a real perception of pain and certainly functional MRI studies have born that out recently. So, sympathetic blockade overall as opposed to the adult literature appears to be less helpful in pediatric CRPS in part because of some of these phenomena, but there is a subgroup of patients that we still put through this treatment regimen that benefit from spinal analgesia more as a springboard to increasing their participation in functional rehabilitation, physical therapy and cognitive/behavioral therapies.

Rehabilitative treatment remains the cornerstone of therapy, as it is I think as well in the adult literature. There was a Children's Hospital study published in Journal of Pediatrics in 2002, looking at the use of rehabilitative treatment in this population. Physical therapy once, versus three times per week, with cognitive behavioral therapy, once per week for six weeks was provided. And that was the comparison. 28 (twenty-eight) patients completed the protocol and the measures that were looked at to assess efficacy were pain scores; gait; stair climbing; psych inventories; regional and systemic autonomic examinations; and quantitative sensory testing looking at small fiber function.

And in the outcome of both groups, both physical therapy once a week and physical therapy three times a week showed a greater than 50% (fifty-percent) improvement in their visual analog pain scores. There was improved gait and stair climbing, and most patients relinquished their assistive devices by 6 (six) weeks, which is an excellent response to rehabilitative therapy.

Therefore, in the pediatric population, we still hold the dogma that the primary treatment objectives are to prevent atrophy and to restore function; that patients really need to embrace the course of functional rehabilitation above all, and that analgesic interventions, intraspinal injections of medications and even less use in our population, nerve blockade, are really just adjutant's to allow the patient to experience a functional rehabilitation program actively to the best ability that they can have.

Therefore, in the pediatric population, we still hold the dogma that the primary treatment objectives are to prevent atrophy and to restore function; that patients really need to embrace the course of functional rehabilitation above all, and that analgesic interventions, intraspinal injections of medications and even less use in our population, nerve blockade, are really just adjutant's to allow the patient to experience a functional rehabilitation program actively to the best ability that they can have.

And so, in having that discussion when we meet with our patients in clinic, we usually sit down and provide feedback to the family and try to explain the issue of neuropathic pain as not being a protective pain, but being a pain that is something that does not mean that they should stop their functional activity. And so, we provide information to the patients and the parents about neuropathic pain, saying that ordinary pain is what you feel when the normal nerves send messages from the inflamed or injured body tissues; and that nerve pain is really caused by abnormal messages sent by the nerve, even after tissue healing.

We explain the issues of nervous system elasticity. We validate the patients pain as being real, but that the information ultimately received at the most rostral center, the cortex, is wrong; that people with nerve pain are not crazy, but the cognitive behavioral therapy is an inmate part of functional rehabilitation; and that treatment of nerve pain involves working through the pain and re-programming the nerves to send the messages properly.

This is sometimes a very difficult message, but we emphasize always to the pediatric population that the prognosis for pediatric chronic regional pain syndrome is generally good. And that we hope that opioid treatment when used appropriately in the population is a brief adjuvant, as are other adjuvant therapies for most children who have this neuropathic pain syndrome. Thanks.

Click Here For Dr. LeBel's References

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Dr. LeBel, thank you very much. I think what you've really helped us do is put the whole problem of chronic pain into a much, much broader perspective, looking at multiple modalities in managing these patients.

We're very fortunate to have with us today at a remote site, at Johns Hopkins University, Dr. Sabine Kost-Byerly. Dr. Kost-Byerly has probably seen some of the worst-of-the-worst in children that have chronic pain syndromes, in particular patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy. And I've asked her to join us today because, I think we really want to make sure we explore all of the potential treatment options, and that we look at where the opioids fit in...into the bigger picture. And I think if we can understand children, which are the most challenging, with all the problems they have from an emotional standpoint and so forth, I think the adults become a piece of cake. Dr. Kost-Byerly? We're very fortunate to have with us today at a remote site, at Johns Hopkins University, Dr. Sabine Kost-Byerly. Dr. Kost-Byerly has probably seen some of the worst-of-the-worst in children that have chronic pain syndromes, in particular patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy. And I've asked her to join us today because, I think we really want to make sure we explore all of the potential treatment options, and that we look at where the opioids fit in...into the bigger picture. And I think if we can understand children, which are the most challenging, with all the problems they have from an emotional standpoint and so forth, I think the adults become a piece of cake. Dr. Kost-Byerly?

Dr. Kost-Byerly:

Yes! I wanted to first thank you for this wonderful opportunity to participate in this symposium. I think it's an exciting new tool and I think it's something that should be explored further in the future as well.

I listened carefully to Dr. LeBel's presentation and I would agree with her and most of it. I think the patients I've seen in Boston are similar to what we see here. This is a Tertiary Care Medical Center, so most of the patients that I would see in the clinic or for in-patient therapy are rather complex and might have failed therapy in other locations.

We use a multi-disciplinary approach to the treatment of RSD. The primary tools are as Dr. Lebel said, physical therapy, behavioral intervention; and they will lead to an improvement in the majority of patients. We do use opioids as adjuncts to the therapy, though not as the first pharmacological intervention, but usually as the third, fourth or fifth.

I see that there are essentially three forms for the treatment of opioids. The one that we use probably most frequently and intermittently is to facilitate physical therapy, or to treat acute increases in pain due to other activities throughout the day. We will use, in a certain patient population, long-acting opioids at night if the patients report to me that they have poor sleep due to pain. This is not as a sleep agent, but really it's a poor initiation of sleep, or poor...they do wake up in the middle of the night because of pain; and then we will attempt to treat them with a long-acting opioid to see whether this will improve.

Finally, there is the around-the-clock treatment. This is really a very small sub-group of patients. In this population, the goal is an increase in function activity and the quality of life. For a child that usually means the child will be able to return to school; participate in activities with a peer group; that should be the goal. When around-the-clock opioids are used, then the treatment should be re-assess at regular intervals, then every few months to check for the continued need and the effect. As I said, that is a small sub-group.

For my in-patients, it's not unusual, because a lot of them have severe pain, are very hesitant to participate in physical therapy programs. It's not unusual then that we will use a peri-spinal infusion, like a lumbar epidural catheter with local anesthetic and opioids and try to alleviate some of the fears of this patient so that they will participate in physical therapy more easily and a little bit more ready to do this.

There is one point that has not been mentioned by previous speakers, but I think it is important in the pediatric population. I'm a little bit hesitant to provide long-term opioid therapy in children adolescents, not necessarily because of development of tolerance or the development of addiction, which I think is pretty rare; but I'm worried in this population particularly about the long-term effects of opioids in the developing body. Opioid therapy, as Dr. Kiefer in Germany said, can result in abnormal endocrine effects and can result in hypogonadism, and lead to low levels of testosterone and estrogen. And, we don't really know what this means for an adolescent, a child going through puberty. So, the risk of osteoporosis or mood changes, or how this will influence the immune system...there are really still many questions, so I think I would be very hesitant to provide long-term opioid therapy in an adolescent patient.

This is what I have to add to this discussion at this point.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Dr. Kost-Byerly, thank you very much. I know that there's nothing like experience in trying to navigate through this, through all of the treatment modalities that are available, especially in children. At this point, what I would like to ask Dr. LeBel to please standby. ...Dr. Lebel, could you please stand by here?

Dr. LeBel:

Yes!

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Because I'm going to come back to you in just a second here.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

What I'd like to do at this point is to go ahead and try to put together, start to put together, construct a "Take-Home Message" thing.

And, what I want to do I guess, first of all, is to kind of weigh in with my two-cents. So, I was taking notes as we went through these presentations and here's what I got out of it, and then I'm going to invite each of our speakers to contribute something more to that.

First, opioid therapy should be considered in anyone with moderate to severe pain. There is no evidence that there is any characteristic in a given patient that imparts a total resistance to the analgesic effects of opioids. But, every case requires the physician to weigh the factors that would influence opioid therapy sooner, rather than later, after other treatment modalities have been tried. We've heard a beautiful discussion of that with Dr. LeBel and Dr. Kost-Byerly about how they've tried to navigate in placing, positioning the opioid in the proper clinical context.

Point number 2 (two). Opioid therapy is not easy; and you said that (Dr. Kirkpatrick speaking to Dr. Marsha Brown), it's not easy, it's very difficult. What does it really require? It requires us starting with a comprehensive assessment of the patient, which includes looking at the issue of potential addiction, aberrant behavior and so forth as part of our assessment. It requires a certain knowledge base about the adverse effects of opioids, and we have to have knowledge about addiction medicine, that's important. We have to have certain skills, certain experience in order to navigate our way most effectively with these patients.

Documentation was noted, the importance of documentation...Dr. Savage brought that up; Dr. Brown, you brought that out as being very, very important...contracts with the patients.

Communication, very important. Communicating with the patient, communicating with the primary care physician. As pain experts, we depend on them to care for these patients. We have to consider their preferences, their resources and so how do we do that? We educate them. that's our job. We have to do that. And of course, the patient can't make an informed decision without being informed about some of these potential problems we've talked about... as Dr. Kost-Byerly pointed out, what about the long-term effects in children on the pituitary axis? So, all of these things are important.

A third point that I think needs to be pointed out here is that, although there's nobody that's resistant, chronic therapy with opioids but opioid therapy might unmask problems. And we've talked in great detail about those things: intolerable side effects; unmanageable side effects; addictive disease. We've discussed the importance to always be aware of the problem, the potential problem of pseudo- addiction.

And we also talked about that not all opioids are the same: methadone is really, really quite different than the other opioids; transdermal fentanyl: there's some patient's where this drug has been a Godsend at 400 mcg patches changed every 2 (two) to 3 (three) days, being required to make them functional. So, they're not all the same and this was something, of course, that Dr. Kiefer brought to our attention.

Dr. Savage at Dartmouth pointed out the potential advantages of long-acting opioids and the fact that you have the slow onset and that you have less risk of this rush, this dancing with the medicine, and of course, it's a little easier to comply in that situation. But I think the point that was made that's very important, there are very few absolutes; each patient is an individual. Maybe a short-acting opioid on a chronic basis for chronic pain would be more appropriate in some patients.

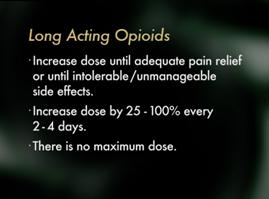

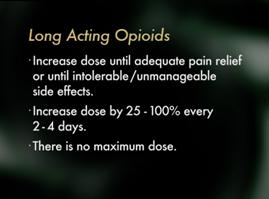

Now, I think what the audience really wants to hear from us today, I really believe this, if I'm sitting out there this is what I want to know: How do I use these opioids, particularly long-acting opioids? So, I'm going to highlight very quickly here, what I think some basic...what a basic roadmap might look like, and I'll invite all of you to comment on this.

I would suggest that maybe when you're starting a long-acting opioid that you may increase the dose until you get adequate pain relief, or, you get intolerable or unmanageable side effects. I would suggest that you increase the dose by 25% to 100% every two to four days. There is no maximum dose! There is no maximum dose for these medications. I think that's a very important concept. You increase the dose until you're limited by toxicity, or one of these other problems related to addiction medicine that would limit you in your prescribing. I would suggest that maybe when you're starting a long-acting opioid that you may increase the dose until you get adequate pain relief, or, you get intolerable or unmanageable side effects. I would suggest that you increase the dose by 25% to 100% every two to four days. There is no maximum dose! There is no maximum dose for these medications. I think that's a very important concept. You increase the dose until you're limited by toxicity, or one of these other problems related to addiction medicine that would limit you in your prescribing.

Now I would like our speakers to offer their take-home messages and I'd like to start with Dr. Kiefer. Are you still with us in Germany?

Dr. Kiefer:

Yes. I am still with you.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

So, you tell me what you think the take-home message should be from this conference.

Dr. Kiefer:

Dr. Kiefer:

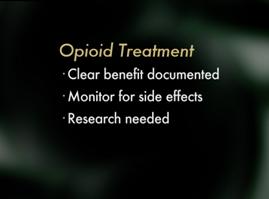

OK. We think that the take-home message should be that nobody should be withheld opioids if the patient needs opioid treatment. However, we would like to emphasize that it's very important to show that opioid treatment for the individual patient results in a clear benefit, that is a significant pain relief for the patient. We would also like to emphasize that neither the physician's nor the patient should fear adverse side effects. We would point out that opioid therapy has to be monitored very closely and physician's need to watch for those side effects and treat and sufficiently, and above all, very early.

And our last remark is that everybody involved should be stimulated to work on providing sufficient evidence to perform scientific studies to finally provide some high quality evidence in the treatment of opioids for neuropathic pain and especially CRPS. Thank you.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Dr. Kiefer, thank you very much. Dr. Butler?

Dr. Butler:

Yes.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Welcome back!

Dr. Butler:

Thank you.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Did you go out sailing while we were talking, or did you hear the discussion we were having?

Dr. Butler:

Oh, no, no! I've been listening to the discussion, very interesting.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

OK, good. Well listen, give us your perspective, give us your take on the take-home message, please.

Dr. Butler:

Dr. Butler:

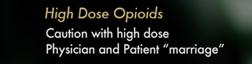

Well, I think if we think of about complex regional pain syndrome use of opioids, you have to think of two uses. One is an acute use to facilitate therapy, and that's probably the best use. The second is chronic long-term use when therapies haven't been very helpful. I'm a little more conservative than you are in use of opioids. You're recommendations sound to me like those for pain in cancer patients, and my experience over time is that we always have been sent the patients on high-dose opioids with the problems, and had to deal with that. And many of those patients on detoxification were significantly better than they were on the high-dose opioids, so you have to be a little careful in how far you go with high-dose opioids.

Another thought is that if you do embark on opioids, especially high-dose opioids for long term treatment, then you marry that patient, because no other practitioner will take over that care. And so, you have to think about not only what's going to happen next week or next month, but in five years. And so, you need to have a short-term plan as well as a long-term plan. But, it has been a wonderful conference, and I've gotten a lot of very good information from the presentations and thank you for having me there with you.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

And Dr. Butler, thank you for letting us disrupt your vacation. While you were talking, some of your comments resonated pretty heavily here among our panelists in the audience here, so I'm going to ask them to comment a little about...especially about marrying patients. They were both kind of nodding their head a little bit here. Dr. Brown, what is your take-home message from this?

Dr. Brown:

Dr. Brown:

Well, I think there's several. One is obvious, communication. I do think that we have to take a good history and look at the addiction potential, because some of our patients will do quite well on high-dose opioids and they don't have that addiction potential. The one's that do will be the ones that you truly marry and will increase their dose and ultimately, unfortunately, some of those people die in terms of it and so there's always, again, weighing the issues there, I think from the addiction standpoint. It's certainly...I urge all my patients who are in recovery, if they have chronic pain, to let me talk with their physician whose managing their pain, so that we communicate and we talk about what's going on and we form a plan, because we don't want them to be in pain.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Hold on for a moment, Dr. Wilson, I'm going to go over to Dr. Savage to follow up on this theme, and then I'm going to come back to you and ask you a question or two. Dr. Savage?

Dr. Savage:

Yes.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

You've been hearing some of these comments; tell us, what do you think? What would you like the audience to take home?

Dr. Savage:

Dr. Savage:

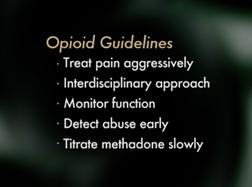

Well, I'll give you my take-home messages from the point of view of the issues that I've been asked to cover, which are more the addiction and abuse issues. So my take-home messages would be first, that we look at the pain associated with CPRS/RSD and at addiction both as medical conditions, which have potential to cause considerable suffering, and we need to attend very closely to each of them. We need to treat pain aggressively and most often that means an interdisciplinary approach, using cognitive/behavioral approaches, physical therapy, perhaps interventionalist procedures and a variety of medications. But when opioids are used, we need to pay close attention to the potential or risk for developing addiction; monitor patients, not only their pain, but their level of function, their mood, their sleep; to be sure that the medications are helping them and improving their quality of life; and to detect abuse or addiction early because these are life threatening problems, detect them early if they occur. If we need to continue opioid therapy in somebody who does develop addiction, we need to partner with somebody who understands the disease of addiction and work together to help that patient receive the pain relief that they need and to monitor their recovery or help get them into recovery.

One final brief comment. I agree with your recommendation to increase 25 to 100% dose of opioids if you're titrating aggressively, if it's appropriate to titrate aggressively, for most opioids, but I would be very cautious titrating methadone that way. We need to start low and go very, very slowly. It takes 7(seven) to 10 (ten) sometimes even 14 (fourteen) days to get stable state of methadone, so we need to titrate a little more slowly. Thank you.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Thank you Dr. Savage. Dr. Wilson, what is the take-home message here today?

Dr. Wilson:

Dr. Wilson:

Well, the take-home message, I think that it should be like we're doing. More education at all levels. I think that education is of paramount importance because part of the reason why we have to marry so many patients is because doctors in Primary Care are not comfortable. I mean, in part it's because they don't have appropriate knowledge of opioids, and rightfully so, they should not be doing things that they are not really well informed and prepared and ready to do. But I think it's very important that they get the message that we educate primary care physicians so we can work together, that way our clinics would not be filled with so many patients that we have gotten to be stable, and all we do for a lot of those people is just continue to prescribe and perpetuate prescriptions every 30 days. And then, if we're lucky enough that they take them back, then if the primary care physician is not educated about opioids, in no time the patient is back to us full of problems.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Right, right. Well, it looks like everybody is resonating to that as well. Dr. LeBel?

Dr. LeBel:

Yes.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Tell us what you think from your perspective, particularly as it relates to the pediatric population.

Dr. LeBel:

Dr. LeBel:

Well I think for pediatrics, as emphasized, this is a population that has a generally favorable prognosis, and therefore, opioids as an intervention in this group do adhere more to Dr. Butler's acute use to facilitate functional rehabilitation in all ways, both as in-patients and out-patients and are usually brief courses of intervention and not sustained long term except in very, very, very rare cases. I want to emphasize that we have a chance in pediatrics because of the favorable prognosis, to intervene early and effectively, pushing forward the rehabilitative strategies, adequately treating the pain to allow the child to pursue that type of rehabilitation, and we have the opportunity as practitioners to prevent these patients from going on to having chronic pain disorders, which is a very important mandate. And I would just echo the need for additional research in all type populations, elderly, pediatric and most adults in the use of chronic opioids and acute opioids in neuropathic pain.

Thank you for letting me participate. It has been very educational for me.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Again, thank you Dr. LeBel. Dr. Kost-Byerly?

Dr. Kost-Byerly:

Dr. Kost-Byerly:

Yes, I would agree with Dr. LeBel. I think although opioids are not the first choice of treatment for RSD / CRPS in children, they should be considered as a part of a pharmacological approach within a multidisciplinary management. I also couldn't agree more with Dr. Kiefer in Germany, Dr. LeBel, that more research is needed. I particularly feel that more research is needed for the subgroup of patients that, pediatric patients, that do not respond favorably to the most common physical therapy or behavioral intervention. I feel it is very much in need so we can prevent potentially years of suffering in these patients.

I wanted to say thank you that I was able to participate and I think it was a very exciting symposium.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Well, thank you very much Dr. Kost-Byerly, we're privileged to have you join us today.

QUESTIONS & ANSWERS

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Now, please everybody stand by because, I went back and picked up some of these faxes, some of these questions and, boy, there's some tough questions here. So, I'm going to have to just say just jump right in. Those that are at remote sites and we want to see whose the bravest. This question is asked over and over again, so are you ready for the big question? Here it is.

You have a patient that is on a contract, they break the contract. They have chronic pain, they're suffering. On occasion they may be writhing in pain. They've been into a rehab program, a recovery program and they relapse... you see the question, what do you do? What do you do? Now, don't raise your hands all at once.

Let's take the people at the remote sites first. Is anybody at one of our remote sites either here in the United States or abroad, does anyone want to weigh in on that question?

Dr. Butler:

I can stick my neck out on that one.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Thank you.

Dr. Butler:

This is Dr. Butler talking. I've had several patients like that and I just sit down and talk to them quite frankly and tell them what the problem is: I think you're abusing these medications and I'm not sure you're getting any help from them. And I'll tell them if they fail the contract once, I have the talk; if it happens a second time I warn them, then you've got two options. One is that you can go back to drug treatment program. The second is I will do detox myself and then you have to find another physician if you're going to, if you want to continue taking these medications, because I can't do it under this situation. I don't think they're helpful and I think that the problem is not the pain; it's the drug abuse that's the major problem. And that's what I've done. But, sometimes tough love is what these patients need.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Dr. Butler, once again, what can I tell you. If you had eyes here you'd see that you're getting a lot of people shaking their head in agreement with you. Does anybody else want to weigh in on that question?

Dr. Savage:

Yes, I would. This is Dr. Savage.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Yes, Dr. Savage.

Dr. Savage:

I agree with essentially all of what he has said. I would add though, that it's highly variable the reasons that people break contracts. We have to make an individual assessment of what the reasons for breaking the contract is, and what the facts were, I mean what actually happened. If the person is relapsed into addiction and they have an active addiction disorder, it's probably not safe for them to be using opioid medications, and we need to help them get back into recovery, and be aggressive about doing that and then once in recovery be highly structured in re-providing opioids if we elect to do that, sometimes dispensing even on a daily basis we have done.

The bottom line is to protect the patient, but in the end I think we have to recognize that we can't help all people, and there may be safety issues that are beyond our control. That means that we need to taper people off of opioids, and I would not refer them to somebody else necessarily unless they chose to go to somebody else, but to continue to follow them aggressively with non-opioid approaches to treatment and provide them with support they need for recovery and for pain.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

If I'm hearing you right Dr. Savage, you're saying that...you almost have to...if you want to play this game; you have to anticipate that some of these patients are going to relapse, and you better have a program, you better have a plan in place. Is that what I'm hearing?

Dr. Savage:

Yes, and that pain treatment, the promise and offer of pain treatment, effective pain treatment, may actually be a support for helping them get into recovery.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Good. We have time for one more question. Well, we have a lot of questions, but I think this is a very important question, so I'm going to just lay it out here.

The question is: Patients who develop tolerance to the analgesic effects of opioid, is that a lifetime thing? If they later decide to wean themselves from opiates, do they remain tolerant? Do we have any empirical scientific information, anything that would help us understand that?

And also another question which is related is: What about...what about...do we know...are there some individuals, or some characteristics of individuals that develop tolerance more quickly than others to the opioids? So there's really a 2-part question. Let's take one at a time.

The question is: Is it a permanent change in your body when you develop tolerance to opioids, or do you have a return of your sensitivity to the analgesic effects later on? Who would like to weigh in on that one, anyone either at a remote site or here at the University of South Florida?

Dr. Kost-Byerly:

I could answer this; this is Dr. Byerly from Johns Hopkins.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Thank you Dr. Kost-Byerly.

Dr. Kost-Byerly:

As a Pain Specialist and an Anesthesiologist, I can tell you this from my experience, that when we have trauma patients, other patients on high-dose opioids for a long period of time, who eventually come back to the operating room later, their requirement, if they have been off the medication for a period of time, pretty much is back to normal, so they will have a normal analgesic requirement. Of course, if they are still taking high-dose opioids, that has to be considered and they will have a higher requirement for surgery, potentially.

Dr. Savage:

I think from an addiction medicine perspective, I would give the same response. We know that many people who have been detoxified from illicit opioids say during a jail term, who then go back out on the street, are at a very high risk for overdosing because their tolerance has diminished significantly.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Thank you Dr. Savage. This is very, very important. It is not only important for Pain Specialists, but for the Anesthesiologist that has to provide anesthesia for these patients. Does anybody know if there's a certain characteristic of person who is more likely to develop tolerance than others either in terms of, well for example, age or in terms of other co-existing medical problems, they develop tolerance more quickly? I don't know of anything. Does anybody at any of our remote sites have any data to share on that question?

Dr. Butler:

I don't have any data, but........

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

We're with you Dr. Butler. We hear you.

Dr. Butler:

I don't have any data, but my experience is that the patients who are treating things like anxiety are ones that are more likely to develop rapid tolerance. If they have a pain problem, but they have an underlying anxiety problem that hasn't been well addressed, they're the ones that tend to escalate doses much, much quicker.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Well that certainly makes a lot of sense and I think that some of our panelists here are agreeing with you that in their clinical experience as well, they see the same thing, for sure. So, pain in a way, treating pain itself, is somewhat protective to the developing tolerance to medications, I think that's what I'm hearing from you?

Dr. Kost-Byerly:

Well, in patients, I know that in patients who are treated say, with fentanyl infusions in the ICU, the development of tolerance can be rather rapid. More recently though, that would agree with...I think with Dr. Savage...I think it was Dr. Savage said, the quicker rise in the analgesic blood level, the CSF level, might lead to a higher development, maybe to a quicker development of tolerance. Though more recent studies did not support that for remifentanil, which is even shorter-acting and even more rapid in onset. So, I think it might, if at all, it might depend on the analgesic itself, less so is it on the patient.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Thank you very much Dr. Kost-Byerly. I think we're ready to close this symposium, but before I do, I really, really want to thank the faculty from around the world. I want to thank the staff here at the University of South Florida, this has been a Herculean team effort to make this happen in real time and be interactive the way it has been. And, last but not least, I want to thank the audience for participating in this. We hope that you have gained as much as we have from this experience.

Thank you very much.

ADDENDUM:

WARNING ABOUT METHADONE USE

Physicians must be aware of the particulars of methadone. When switching from opioids with a relatively short half-life (such as hydrocodone and MS-Contin) to methadone, the physician must be aware that methadone has an unusually long half-life and that it might take several days before the patient's blood levels become stabilized. The maximum analgesic AND respiratory depressant effects of a dosing regimen of methadone cannot be determined until a steady state is achieved. Therefore, days of drug accumulation may occur after a period of rapid dose titration. In some cases, this may lead to profound respiratory depression and death. For this reason, methadone is considered a poor choice for patients who are difficult to monitor.

When administering methadone, start low and go slow! For example, the initial rate of titration of methadone could be no more than by 2.5 mg TID for 7 days since there is such a long half-life, blood levels continue to rise during this period. After seven days, the dose could be increased to 5 mg per day for another seven days. IF SEDATION OCCURS OR IF THERE IS A PROBLEM WITH AROUSABILITY, METHADONE SHOULD BE HELD UNTIL THIS CLEARS AND RESTARTED AT A LOWER DOSE. Other shorter acting opioids may be used in the interim to compensate for the slow titration of methadone.

Converting to methadone from other opioids needs to be done with caution. Some researchers propose that methadone is almost 10 times more potent than opioids such as MS-Contin and hydrocodone when treating chronic pain. Calculating a morphine equivalent of methadone is essential for patient safety. Let's assume that prior to switching to methadone, the patient was taking 60 mg of MS-Contin per day plus up to 20 mg of hydrocodone per day for a total of 80 mg of morphine equivalents per day. If the patient was switched to 80 mg of methadone per day, the patient's dose, in effect, would have been abruptly increased from 80 mg per day to 800 mg of morphine equivalents per day.

In addition, when switching an opioid-tolerant patient to an alternative opioid drug, it is wise to assume that cross-tolerance will be incomplete. This means that a patient who has developed tolerance to one opioid analgesic may not be equally tolerant to another. Therefore, when switching to a new opioid, opioid-tolerant patients should be started on a lower dose of the new opioid.

December 1, 2006:

ALERT FROM THE FDA ON METHADONE

FDA ALERT [11/2006]: Death, Narcotic Overdose, and Serious Cardiac Arrhythmias

FDA has reviewed reports of death and life-threatening side effects such as slowed or stopped breathing, and dangerous changes in heart beat in patients receiving methadone. These serious side effects may occur because methadone may build up in the body to a toxic level if it is taken too often, if the amount taken is too high, or if it is taken with certain other medicines or supplements. Methadone has specific toxic effects on the heart (QT prolongation and Torsades de Pointes). Physicians prescribing methadone should be familiar with methadone’s toxicities and unique pharmacologic properties. Methadone’s elimination half-life (8-59 hours) is longer than its duration of analgesic action (4-8 hours). Methadone doses for pain should be carefully selected and slowly titrated to analgesic effect even in patients who are opioid-tolerant. Physicians should closely monitor patients when converting them from other opioids and changing the methadone dose, and thoroughly instruct patients how to take methadone. Healthcare professionals should tell patients to take no more methadone than has been prescribed without first talking to their physician.

This information reflects FDA’s current analysis of data available to FDA concerning this drug. FDA intends to update this sheet when additional information or analyses become available

REFERENCES

Dr. Kiefer's References:

- Kurz A, Sessler DI. Opioid induced bowel dysfunction. Pathophysiology and potential new

treatments. Drugs 2003, 63 (7):648-71

- Foss JF. A review of the potential role of methylnaltrexone in opioid bowel dysfunction.

Am J Surg. 2001 Nov;182(5A Suppl):19S-26S.

- Rogers M, Cerda JJ. The narcotic bowel syndrome.

J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11(2):132-5.

- Wei G, Moss J, Yuan CS. Opioid-induced immunosuppression: is it centrally mediated or peripherally mediated? Biochem Pharmacol. 2003 1;65(11):1761-6.

- Andersen G, Christrup L, Sjogren P. Relationships among morphine metabolism, pain and side effects during long-term treatment: an update.

J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(1):74-91.

- Mao J. Opioid-induced abnormal pain sensitivity: implications in clinical opioid therapy.

Pain. 2002;100(3):213-7.

- Choi YS, Billings JA. Opioid antagonists: a review of their role in palliative care, focusing on use in opioid-related constipation.

J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(1):71-90.

- Mao J, Mayer DJ. Spinal cord neuroplasticity following repeated opioid exposure and its relation to pathological pain.

Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001 Mar;933:175-84.

- Young-McCaughan S, Miaskowski C. Measurement of opioid-induced sedation.

Pain Manag Nurs. 2001;2(4):132-49.

- Eriksen J. Opioids in chronic non-malignant pain.

Eur J Pain. 2001;5(3):231-2.

- Friedman JD, Dello Buono FA. Opioid antagonists in the treatment of opioid-induced constipation and pruritus.

Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35(1):85-91.

- Cherny NI, Thaler HT, Friedlander-Klar H, Lapin J, Foley KM, Houde R, Portenoy RK. Opioid responsiveness of cancer pain syndromes caused by neuropathic or nociceptive mechanisms: a combined analysis of controlled, single-dose studies.

Neurology. 1994;44(5):857-61.

- Portenoy RK, Foley KM, Inturrisi CE. The nature of opioid responsiveness and its implications for neuropathic pain: new hypotheses derived from studies of opioid infusions.

Pain. 1990;43(3):273-86.

- Benedetti F, Vighetti S, Amanzio M, Casadio C, Oliaro A, Bergamasco B, Maggi G. Dose-response relationship of opioids in nociceptive and neuropathic postoperative pain.

Pain. 1998;74(2-3):205-11.

- Rowbotham MC, Twilling L, Davies PS, Reisner L, Taylor K, Mohr D. Oral opioid therapy for chronic peripheral and central neuropathic pain.

N Engl J Med. 2003;348(13):1223-32.

- Harke H, Gretenkort P, Ladleif HU, Rahman S, Harke O. The response of neuropathic pain and pain in complex regional pain syndrome I to carbamazepine and sustained-release morphine in patients pretreated with spinal cord stimulation: a double-blinded randomized study.

Anesth Analg. 2001;92(2):488-95.

- Glynn CJ, Stannard C, Collins PA, Casale R. The role of peripheral sudomotor blockade in the treatment of patients with sympathetically maintained pain.

Pain. 1993;53(1):39-42.

- Dahl JB, Jeppesen IS, Jorgensen H, Wetterslev J, Moiniche S. Intraoperative and postoperative analgesic efficacy and adverse effects of intrathecal opioids in patients undergoing cesarean section with spinal anesthesia: a qualitative and quantitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials.

Anesthesiology. 1999;91(6):1919-27.

- Cherny N, Ripamonti C, Pereira J, Davis C, Fallon M, McQuay H, Mercadante S, Pasternak G, Ventafridda V; Expert Working Group of the European Association of Palliative Care Network. Strategies to manage the adverse effects of oral morphine: an evidence-based report.

J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(9):2542-54.

- Mercadante S, Portenoy RK. Opioid poorly-responsive cancer pain. Part 3. Clinical strategies to improve opioid responsiveness.

J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21(4):338-54.

Dr. Brown's References:

- Miller NS (editor). Comprehensive Handbook of Drug and Alcohol Addiction. Marcel Decker, Inc., New York, 1991.

Editors Allan W. Graham, M.D., FACP, Terry K. Schultz, M.D., FASAM, Michael F. Mayo-Smith, M.D., M.P.H., Richard K. Ries, M.D., and Bonnie B. Wilford. Principles of Addiction Medicine, Third Edition. American Society of Addiction Medicine, Inc. Chevy Chase, Maryland, 2003.

- Morse MD, Robert M., Flavin MD, Daniel K. The Definition of Alcoholism.

JAMA 268:1012-1014, 1992.

Dr. LeBel's References:

- Berde CB, LeBel AA, and Olsson G. Neuropathic pain in children. In Schecter NL, Berde CB, and Yaster, M,eds. Pain in infants, children, and adolescents.

Philadelphia : Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003; 620-641.

- Berde CB, Sethna NF. Analgesics for the treatment of pain in children.

N Engl J Med. 2002; 347, 14:1094-1103.

- Lee BH, Scharff L, Sethna NF, McCarthy CF, Scott-Sutherland J, Shea AM, Sullivan P, Meier P, Zurakowski D Masek BJ, and Berde CB. Physical therapy and cognitive-behavioral treatment fo complex regional pain syndromes.

J Pediatrics. 2002; 141:135-140.

- Robowthan MC, Twilling L, Davies, PS, Reisner L, Taylor K, Mohr D. Oral opioid therapy for chronic peripheral and central neuropathic pain.

New Engl J Med. 2003; 348, 13:1223-1232.

- Truong W, Cheng C, Xu QG, Li XQ, Zochodne, DW. m Opioid receptors and analgesia at the site of a peripheral nerve injury.

Ann Neurol. 2003; 53:366-375.

-

Wilder RT, Berde CB, Wolohan M, Masek BJ, and Micheli LJ. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy in children. Clinical characteristics and follow-up of seventy patients.

J.Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992; 74A:910-919.

Dr. Savage's References

Selected References Related to Abuse and Addiction Issues in Pain Management

American Academy of Pain Medicine, the American Pain Society and the American Society of Addiction Medicine (2001) Joint Public Policy Statement on “Definitions Related to the Use of Opioids in the Treatment of Pain

American Pain Foundation (2001). Promoting Pain Relief and Preventing Abuse of Pain Medications: A Critical Balancing Act. A Joint Statement from 21 Health Organizations and The Drug Enforcement Administration. www.painfoundation.org/page_news.asp.

Clark HW, Sees KL (1988). “Chronic Pain and the Chemical Dependency Specialist.” California Society for the Treatment of Alcoholism and Other Durg Dependencies News 15(1): 1-12.

Collins E, Cesselin F (1991). “Neurobiological Mechanisms of Opioid Tolerance and Dependence.” Clinical Neuropharmacology 14: 465-488.

Compton P, Charuvastra VC, Ling W (2001). “Pain Intolerance in Opioid-Maintained Former Opiate Addicts: Effect of Long-Lasting Maintenance Agent.” Drug & Alcohol Dependence 63(2): 139-46.

Compton P., McCaffery M. (2001 Jan). “Treating Acute Pain in Addicted Patients.” Nursing 31(1): 17.

Doverty M., White JM, Somogyi AA, Bochner F, Ali R, Ling W (2000). “Hyperalgesic Responses in Methadone Maintenance Patients.” Pain 90: 90-96.

Dunbar S, Katz N (1996). “Chronic Opioid Therapy for Nonmalignant Pain in Patients with a History of Substance Abuse: Report of 20 Cases.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 11(3): 163-171.

Emmons KM, Rollnick S (2001 Jan). “Motivational Interviewing in Health Care Setting;s. Opportunities and Limitations.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 20(1): 68-74.

Enoch, MA and Goldman, D (1999). “Genetics of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse.” Psychiatric Clinics of North America 22(2): 289-99.

Federation of State Medical Boards, (1998). “Model Guidelines for the Use of Opioids for the Treatment of Pain.” Bulletin of the Federation of State Medical Boards 85:2: 84-87.

Gardner, E (1997). Brain Reward Mechanisms. Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Text. Lowinson J, Ruiz P and Millman R. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins: 51-85.

Heit, HA (2002). “Addiction, Physical Dependence, and Tolerance: Precise Definitions to Help Clinicians Evaluate and Treat Chronic Pain Patients.”: 1-12.

Jamison RN, Kauffman J, Katz NP (2000 Jan). “Characteristics of Methadone Maintenance Patients with Chronic Pain.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 19(1): 53-62.

Joranson DE, Ryan KM, Gilson AM, Dahl JL (2000 Apr). “Trends in Medical Use and Abuse of Opioid Analgesics.” JAMA 83(13): 1710-1778.

Kalt, RB (1997). Twelve Step Recovery from Alcoholism, Drug Addiction and Chronic Physical Pain.

Kennedy J, Crowley T (1990). “Chronic Pain and Substance Abuse: A Pilot Study of Opioid Maintenance.” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 7: 233-238.

Kirsh KL, Whitcomb LA, Donaghy K, Passik SD (2002). “Abuse and Addiction Issues in Medically Ill Patients with Pain: Attempts at Clarification of Terms and Empirical Study.” The Clinical Journal of Pain 18: S52-S60.

Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Damron KS, Beyer CD, Barnhill RC (2003). “Prevalence of Illicit Drug Use in Patients without Controlled Substance Abuse in Interventional Pain Management.” Pain Physician 6: 173-178.

McPherson TL, Hersch RK (2000). “Brief Substance Use Screening Instruments for Primary Care Settings: A Review.” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 18(2): 193-202.

Moryl N, Santiago-Palma J, Kornick C, Derby S, Fischberg D, Payne R, Manfredi PL (2002). “Pitfalls of Opioid Rotation: Substituting Another Opioid for Methadone in Patients with Cancer Pain.” Pain 96: 325-328.

Pasero CL, Compton P. (1997 Apr). “Managing Pain in Addicted Patients.” American Journal of Nursing 97(4): 17-8.

Passik SD, Portenoy RK, Ricketts PL (1998). “Substance Abuse Issues in Cancer Patients. Part 1: Prevalence and Diagnosis.” Oncology (Huntington) 12(4): 517-21,524.

Passik SD, Portenoy RK, Ricketts PL (1998). “Substance Abuse Issues in Cancer Patients. Part 2: Evaluation and Treatment.” Oncology (Huntington) 12(5): 729-34, discussion 736, 741-2.

Pastemak, Gavril W. (2001). “Incomplete Cross Tolerance and Multiple Mu Opioid Petptide Receptors.” Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 22(2): 67-70.

Portenoy, Russell K;Joseph, Herman , Lowinson, Joyce .;Rice, Carolyn; Segal, Sharon , ; Richman, Beverly L.;Dole VP (1997). “Pain Management and Chemical Dependency: Evolving Perspectives.” JAMA 278(7): 592-593.

Savage, SR (2002). “Assessment for Addiction in Pain-Treatment Settings.” The Clinical Journal of Pain 18: S28-S38.

Scimeca MM, Savage SR, Portenoy R, Lowinson J (2000). “Treatment of Pain in Methadone-Maintained Patients.” The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine 67(5&6): 412-422.

Sees KL, Clark W (1993). “Opioid Use in the Treatment of Chronic Pain: Assessment of Addiction.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 8(5): 257-264.

Van Ree JM, Gerrits MA, Vanderschuren LJ (1999 Jun). “Opioids, Reward and Addiction: An Encounter of Biology, Psychology, and Medicine.” Pharmacological Reviews 51(2): 341-96.

Vourakis, C (1998). “Substance Abuse Concerns in the Treatment of Pain.” Nursing Clinics of North America 33(1): 47-60.

Wesson D, Ling W, Smith D (1993). “Prescription of Opioids for Treatment of Pain in Patients with Addictive Disease.” Journal of Pain & Symptom Management 8(5): 289-296.

HOME | MENU |

CONTACT US

The International Research Foundation

for RSD / CRPS is a

501(c)(3) (not-for-profit) organization in the United States of America.

Copyright © 2003 International

Research Foundation for RSD / CRPS.

All rights reserved.

For permission to reprint any information on the website, please contact

the Foundation.

|

This year we are taking a different approach. This year we will be using advanced technology.

For the first time this University's College Of Medicine will conduct a live and interactive health

symposia to a worldwide audience of health professionals using the Internet. In a few moments we will

engage experts from Germany, from Sweden, as well as from universities throughout the United States

in a live, interactive discussion over the Internet. This symposium will focus on the use of

opioids to treat RSD in both adults and in children.

This year we are taking a different approach. This year we will be using advanced technology.

For the first time this University's College Of Medicine will conduct a live and interactive health

symposia to a worldwide audience of health professionals using the Internet. In a few moments we will

engage experts from Germany, from Sweden, as well as from universities throughout the United States

in a live, interactive discussion over the Internet. This symposium will focus on the use of

opioids to treat RSD in both adults and in children. Now, allow me to introduce our outstanding panel in the room. To my immediate left we have Dr. Maria

Carmen Wilson of the Department of Neurology at the University of South Florida. Dr. Wilson is Director

of the Pain Management Program at Tampa General Hospital. She is widely published in the field of chronic

pain headaches.

Now, allow me to introduce our outstanding panel in the room. To my immediate left we have Dr. Maria

Carmen Wilson of the Department of Neurology at the University of South Florida. Dr. Wilson is Director

of the Pain Management Program at Tampa General Hospital. She is widely published in the field of chronic

pain headaches.

I cannot think of someone more qualified to discuss this topic than Dr.Thomas

Kiefer in Germany and as I've noted, Dr. Kiefer has been collaborating with

Dr. Schwartzman, so we're going to see some very cutting-edge research that's

going on in trying to find, hopefully, a potential cure, or at least a way to

put these patients in some type of partial remission. The reason I can say

that Dr. Kiefer is an expert on Adverse Effect is because his colleague, Dr.

Rohr and he have been doing this research at their University the Eberhard-Karls

University Medical School in Germany. Their research with the NMDA-antagonist

Ketamine shows great promise in the treatment of advanced RSD.

I cannot think of someone more qualified to discuss this topic than Dr.Thomas

Kiefer in Germany and as I've noted, Dr. Kiefer has been collaborating with

Dr. Schwartzman, so we're going to see some very cutting-edge research that's

going on in trying to find, hopefully, a potential cure, or at least a way to

put these patients in some type of partial remission. The reason I can say

that Dr. Kiefer is an expert on Adverse Effect is because his colleague, Dr.

Rohr and he have been doing this research at their University the Eberhard-Karls

University Medical School in Germany. Their research with the NMDA-antagonist

Ketamine shows great promise in the treatment of advanced RSD. Dr. Kiefer:

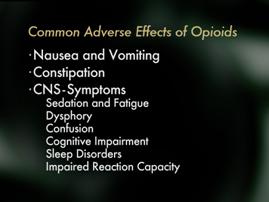

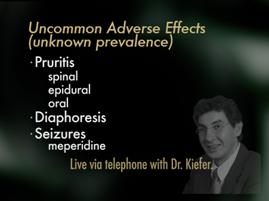

Dr. Kiefer: Most of the side effects are clinically seen when the treatment with

opioids is started, and many of them improve or even disappear in the

course of treatment.

Most of the side effects are clinically seen when the treatment with

opioids is started, and many of them improve or even disappear in the

course of treatment. The side effects listed in this slide are either uncommon or the exact prevalence

is not known. Pruritis or a severe itching feeling is currently thought to be an

effect on the central nervous system. It is rarely seen when opioids are given

orally, but is very common after epidural and intrathecal use. Dahl and colleagues

reported in 1999 in Anesthesiology, an incidence of pruritis of 51% after the

use of spinal morphine. Unclear are data concerning the effects of opioids on

diuresis. The existing data were reported in the 1950's to 1970's, mostly collected

peri-operatively and most of the reported effects are currently thought to

relate to inadequate peri-operative fluid management, rather than to a specific

opioid effect.

The side effects listed in this slide are either uncommon or the exact prevalence

is not known. Pruritis or a severe itching feeling is currently thought to be an

effect on the central nervous system. It is rarely seen when opioids are given

orally, but is very common after epidural and intrathecal use. Dahl and colleagues

reported in 1999 in Anesthesiology, an incidence of pruritis of 51% after the

use of spinal morphine. Unclear are data concerning the effects of opioids on

diuresis. The existing data were reported in the 1950's to 1970's, mostly collected

peri-operatively and most of the reported effects are currently thought to

relate to inadequate peri-operative fluid management, rather than to a specific

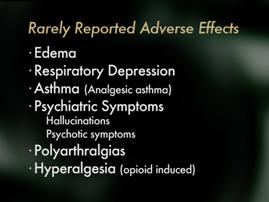

opioid effect. Last, but not least, there remains some very rare side effects of opioids resulting from single or very small case reports. These include: edema, or the accumulation of fluid, above all in the lower extremities, probably caused by a peripheral venous pooling that occurs under opioid therapy. Other psychiatric symptoms, mainly hallucinations and psychotic symptoms have been reported. Respiratory depression is known to be a specific effect of opioids. However, in the presence of severe pain, which is a strong respiratory stimulus, respiratory depression is clinically almost irrelevant when opioid therapy is used at the right indications and carried out correctly.

Last, but not least, there remains some very rare side effects of opioids resulting from single or very small case reports. These include: edema, or the accumulation of fluid, above all in the lower extremities, probably caused by a peripheral venous pooling that occurs under opioid therapy. Other psychiatric symptoms, mainly hallucinations and psychotic symptoms have been reported. Respiratory depression is known to be a specific effect of opioids. However, in the presence of severe pain, which is a strong respiratory stimulus, respiratory depression is clinically almost irrelevant when opioid therapy is used at the right indications and carried out correctly. Dr. Butler began his career as a pain management specialist at the University of Washington. There, he ran the Pain Management Program. For those of you that are experts in the field of pain, you know that is where John Bonica started a pain management program. That program is highly regarded all over the world as being a leader in pain management. From there, he went to Sweden, and there at Uppsala University, he's now the director of their Pain Management Program. One of the areas of his current research is focusing on the impact of immobilization on exacerbating the syndrome reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Dr. Butler, are you with us here?

Dr. Butler began his career as a pain management specialist at the University of Washington. There, he ran the Pain Management Program. For those of you that are experts in the field of pain, you know that is where John Bonica started a pain management program. That program is highly regarded all over the world as being a leader in pain management. From there, he went to Sweden, and there at Uppsala University, he's now the director of their Pain Management Program. One of the areas of his current research is focusing on the impact of immobilization on exacerbating the syndrome reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Dr. Butler, are you with us here? Now, we're going to move on to the second topic here which is addiction, aberrant drug behavior, that sort of thing while on opioids.

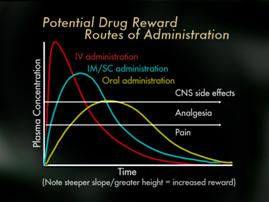

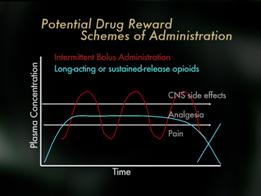

Now, we're going to move on to the second topic here which is addiction, aberrant drug behavior, that sort of thing while on opioids. Now, medication use patterns may also impact addiction risk when opioids are used for pain and some factors include the routes of administration, schedules of administration and certain receptor effects. It is well understood by Addictionists that the more rapid the increase in blood/brain levels of a drug, the more likely it is to cause a rush or a high, which is often termed a reward which may, with repetition, trigger addiction in vulnerable individuals that theoretically, we'd expect opioids use by rapid IV (intravenous) bolus to propose more risk for vulnerable individuals than the use of oral opioids.

Now, medication use patterns may also impact addiction risk when opioids are used for pain and some factors include the routes of administration, schedules of administration and certain receptor effects. It is well understood by Addictionists that the more rapid the increase in blood/brain levels of a drug, the more likely it is to cause a rush or a high, which is often termed a reward which may, with repetition, trigger addiction in vulnerable individuals that theoretically, we'd expect opioids use by rapid IV (intravenous) bolus to propose more risk for vulnerable individuals than the use of oral opioids. Finally, mu opioid receptors appear to be more involved in stimulation of psychic reward, that rush and high, than kappa or other opioid receptors. Therefore, kappa analgesic agonists such as pentazocine and butorphanol may pose less risk than mu opioid receptors, but of course the use of these for pain is limited by their ceiling effects, and because they may reverse mu analgesia in persons who are dependent on mu opioid analgesics. Partial mu agonists such as tramadol or buphinorphene may also have less abuse potential, though their use as analgesics is also fairly limited. Importantly, some studies suggest that pain may actually interfere with the reward effects of opioids so that the risk of addiction to administered opioids may be lower when pain is present then in the absence of pain.

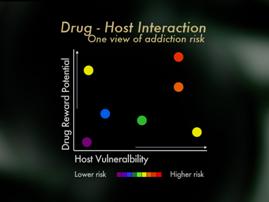

Finally, mu opioid receptors appear to be more involved in stimulation of psychic reward, that rush and high, than kappa or other opioid receptors. Therefore, kappa analgesic agonists such as pentazocine and butorphanol may pose less risk than mu opioid receptors, but of course the use of these for pain is limited by their ceiling effects, and because they may reverse mu analgesia in persons who are dependent on mu opioid analgesics. Partial mu agonists such as tramadol or buphinorphene may also have less abuse potential, though their use as analgesics is also fairly limited. Importantly, some studies suggest that pain may actually interfere with the reward effects of opioids so that the risk of addiction to administered opioids may be lower when pain is present then in the absence of pain. In summary, looking at things from a clinical perspective, it's helpful to view the risk of addiction when opioids are used for pain as an interaction of host vulnerability and pattern of medication use. From the patient perspective, if one has no personal, no family history of addiction, one can generally feel confident that opioids are safe and effective when used as directed, and that the risk of becoming addicted to the medications is low. For patients who do have an addictive disorder, or known risk of an addictive disorder, these patients can also achieve relief with opioids, but it is important that they and their doctors' use special care. It is important that individual lets their physician know of their addiction history, pays close attention to cultivating addiction recovery, takes special care to use medications only as directed, and consider in some circumstance having a partner monitor their use of the medication.

In summary, looking at things from a clinical perspective, it's helpful to view the risk of addiction when opioids are used for pain as an interaction of host vulnerability and pattern of medication use. From the patient perspective, if one has no personal, no family history of addiction, one can generally feel confident that opioids are safe and effective when used as directed, and that the risk of becoming addicted to the medications is low. For patients who do have an addictive disorder, or known risk of an addictive disorder, these patients can also achieve relief with opioids, but it is important that they and their doctors' use special care. It is important that individual lets their physician know of their addiction history, pays close attention to cultivating addiction recovery, takes special care to use medications only as directed, and consider in some circumstance having a partner monitor their use of the medication.

So, first I just wanted to just show a photo of one of our patients who also, although not seen in this photo, had lower extremity involvement at the time of her initial presentation; and of course the effected limb in this photo at this time is on the right side.

So, first I just wanted to just show a photo of one of our patients who also, although not seen in this photo, had lower extremity involvement at the time of her initial presentation; and of course the effected limb in this photo at this time is on the right side.  Therefore, in the pediatric population, we still hold the dogma that the primary treatment objectives are to prevent atrophy and to restore function; that patients really need to embrace the course of functional rehabilitation above all, and that analgesic interventions, intraspinal injections of medications and even less use in our population, nerve blockade, are really just adjutant's to allow the patient to experience a functional rehabilitation program actively to the best ability that they can have.

Therefore, in the pediatric population, we still hold the dogma that the primary treatment objectives are to prevent atrophy and to restore function; that patients really need to embrace the course of functional rehabilitation above all, and that analgesic interventions, intraspinal injections of medications and even less use in our population, nerve blockade, are really just adjutant's to allow the patient to experience a functional rehabilitation program actively to the best ability that they can have. We're very fortunate to have with us today at a remote site, at Johns Hopkins University, Dr. Sabine Kost-Byerly. Dr. Kost-Byerly has probably seen some of the worst-of-the-worst in children that have chronic pain syndromes, in particular patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy. And I've asked her to join us today because, I think we really want to make sure we explore all of the potential treatment options, and that we look at where the opioids fit in...into the bigger picture. And I think if we can understand children, which are the most challenging, with all the problems they have from an emotional standpoint and so forth, I think the adults become a piece of cake. Dr. Kost-Byerly?

We're very fortunate to have with us today at a remote site, at Johns Hopkins University, Dr. Sabine Kost-Byerly. Dr. Kost-Byerly has probably seen some of the worst-of-the-worst in children that have chronic pain syndromes, in particular patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy. And I've asked her to join us today because, I think we really want to make sure we explore all of the potential treatment options, and that we look at where the opioids fit in...into the bigger picture. And I think if we can understand children, which are the most challenging, with all the problems they have from an emotional standpoint and so forth, I think the adults become a piece of cake. Dr. Kost-Byerly? I would suggest that maybe when you're starting a long-acting opioid that you may increase the dose until you get adequate pain relief, or, you get intolerable or unmanageable side effects. I would suggest that you increase the dose by 25% to 100% every two to four days. There is no maximum dose! There is no maximum dose for these medications. I think that's a very important concept. You increase the dose until you're limited by toxicity, or one of these other problems related to addiction medicine that would limit you in your prescribing.

I would suggest that maybe when you're starting a long-acting opioid that you may increase the dose until you get adequate pain relief, or, you get intolerable or unmanageable side effects. I would suggest that you increase the dose by 25% to 100% every two to four days. There is no maximum dose! There is no maximum dose for these medications. I think that's a very important concept. You increase the dose until you're limited by toxicity, or one of these other problems related to addiction medicine that would limit you in your prescribing. Dr. Kiefer:

Dr. Kiefer: Dr. Butler:

Dr. Butler: Dr. Savage:

Dr. Savage:

Dr. Kost-Byerly:

Dr. Kost-Byerly: